Project: kaleido

Static image export for web-based visualization libraries with zero dependencies

Project Details

- Latest version

- 0.2.1.post1

- Home Page

- PyPI Page

- https://pypi.org/project/kaleido/

Project Popularity

- PageRank

- 0.0034705728888539066

- Number of downloads

- 1789161

Overview

Kaleido is a cross-platform library for generating static images (e.g. png, svg, pdf, etc.) for web-based visualization libraries, with a particular focus on eliminating external dependencies. The project's initial focus is on the export of plotly.js images from Python for use by plotly.py, but it is designed to be relatively straight-forward to extend to other web-based visualization libraries, and other programming languages. The primary focus of Kaleido (at least initially) is to serve as a dependency of web-based visualization libraries like plotly.py. As such, the focus is on providing a programmatic-friendly, rather than user-friendly, API.

Installing Kaleido

The kaleido package can be installed from PyPI using pip...

$ pip install kaleido

or from conda-forge using conda.

$ conda install -c conda-forge python-kaleido

Releases of the core kaleido C++ executable are attached as assets to GitHub releases at https://github.com/plotly/Kaleido/releases.

Use Kaleido to export plotly.py figures as static images

Versions 4.9 and above of the Plotly Python library will automatically use kaleido for static image export when kaleido is installed. For example:

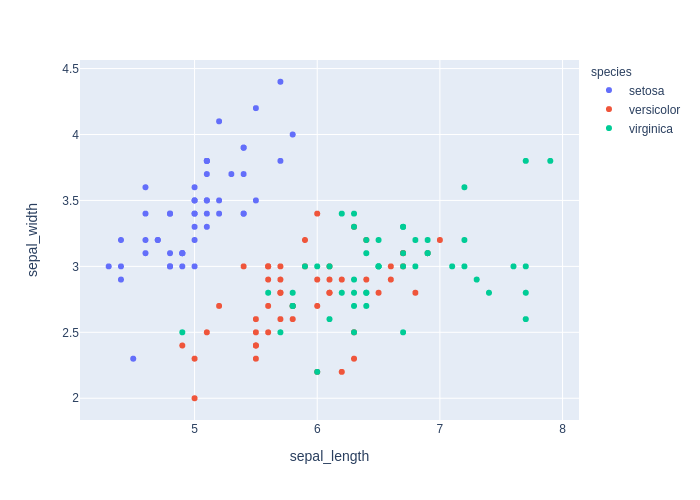

import plotly.express as px

fig = px.scatter(px.data.iris(), x="sepal_length", y="sepal_width", color="species")

fig.write_image("figure.png", engine="kaleido")

Then, open figure.png in the current working directory.

See the plotly static image export documentation for more information: https://plotly.com/python/static-image-export/.

Low-level Kaleido Scope Developer API

The kaleido Python package provides a low-level Python API that is designed to be used by high-level plotting libraries like Plotly. Here is an example of exporting a Plotly figure using the low-level Kaleido API:

Note: This particular example uses an online copy of the plotly JavaScript library from a CDN location, so it will not work without an internet connection. When the plotly Python library uses Kaleido (as in the example above), it provides the path to its own local offline copy of plotly.js and so no internet connection is required.

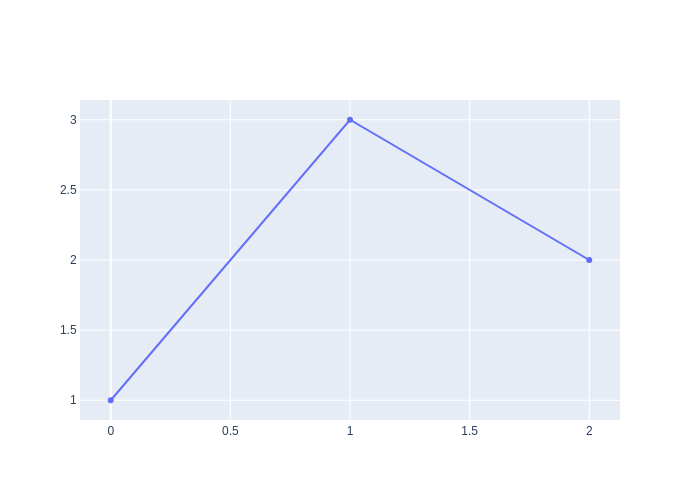

from kaleido.scopes.plotly import PlotlyScope

import plotly.graph_objects as go

scope = PlotlyScope(

plotlyjs="https://cdn.plot.ly/plotly-latest.min.js",

# plotlyjs="/path/to/local/plotly.js",

)

fig = go.Figure(data=[go.Scatter(y=[1, 3, 2])])

with open("figure.png", "wb") as f:

f.write(scope.transform(fig, format="png"))

Then, open figure.png in the current working directory.

Background

As simple as it sounds, programmatically generating static images (e.g. raster images like PNGs or vector images like SVGs) from web-based visualization libraries (e.g. Plotly.js, Vega-Lite, etc.) is a complex problem. It's a problem that library developers have struggled with for years, and it has delayed the adoption of these libraries among scientific communities that rely on print-based publications for sharing their research. The core difficulty is that web-based visualization libraries don't actually render plots (i.e. color the pixels) on their own, instead they delegate this work to web technologies like SVG, Canvas, WebGL, etc. Similar to how Matplotlib relies on various backends to display figures, web-based visualization libraries rely on a web browser rendering engine to display figures.

When the figure is displayed in a browser window, it's relatively straight-forward for a visualization library to provide an export-image button because it has full access to the browser for rendering. The difficulty arises when trying to export an image programmatically (e.g. from Python) without displaying it in a browser and without user interaction. To accomplish this, the Python portion of the visualization library needs programmatic access to a web browser's rendering engine.

There are three main approaches that are currently in use among Python web-based visualization libraries:

- Bokeh, Altair, bqplot, and ipyvolume rely on the Selenium Python library to control a system web browser such as Firefox or Chrome/Chromium to perform image rendering.

- plotly.py relies on Orca, which is a custom headless Electron application that uses the Chromium browser engine built into Electron to perform image rendering. Orca runs as a local web server and plotly.py sends requests to it using a local port.

- When operating in the Jupyter notebook or JupyterLab, ipyvolume also supports programmatic image export by sending export requests to the browser using the ipywidgets protocol.

While approaches 1 and 2 can both be installed using conda, they still rely on all of the system dependencies of a complete web browser, even the parts that aren't actually necessary for rendering a visualization. For example, on Linux both require the installation of system libraries related to audio (libasound.so), video (libffmpeg.so), GUI toolkit (libgtk-3.so), screensaver (libXss.so), and X11 (libX11-xcb.so) support. Many of these are not typically included in headless Linux installations like you find in JupyterHub, Binder, Colab, Azure notebooks, SageMaker, etc. Also, conda is still not as universally available as the pip package manager and neither approach is installable using pip packages.

Additionally, both 1 and 2 communicate between the Python process and the web browser over a local network port. While not typically a problem, certain firewall and container configurations can interfere with this local network connection.

The advantage of options 3 is that it introduces no additional system dependencies. The disadvantage is that it only works when running in a notebook, so it can't be used in standalone Python scripts.

The end result is that all of these libraries have in-depth documentation pages on how to get image export working, and how to troubleshoot the inevitable failures and edge cases. While this is a great improvement over the state of affairs just a couple of years ago, and a lot of excellent work has gone into making these approaches work as seamlessly as possible, the fundamental limitations detailed above still result in sub-optimal user experiences. This is especially true when comparing web-based plotting libraries to traditional plotting libraries like matplotlib and ggplot2 where there's never a question of whether image export will work in a particular context.

The goal of the Kaleido project is to make static image export of web-based visualization libraries as universally available and reliable as it is in matplotlib and ggplot2.

Approach

To accomplish this goal, Kaleido introduces a new approach. The core of Kaleido is a standalone C++ application that embeds the open-source Chromium browser as a library. This architecture allows Kaleido to communicate with the Chromium browser engine using the C++ API rather than requiring a local network connection. A thin Python wrapper runs the Kaleido C++ application as a subprocess and communicates with it by writing image export requests to standard-in and retrieving results by reading from standard-out. Other language wrappers (e.g. R, Julia, Scala, Rust, etc.) can fairly easily be written in the future because the interface relies only on standard-in / standard-out communication using JSON requests.

By compiling Chromium as a library, we have a degree of control over what is included in the Chromium build. In particular, on Linux we can build Chromium in headless mode which eliminates a large number of runtime dependencies, including the audio, video, GUI toolkit, screensaver, and X11 dependencies mentioned above. The remaining dependencies can then be bundled with the library, making it possible to run Kaleido in minimal Linux environments with no additional dependencies required. In this way, Kaleido can be distributed as a self-contained library that plays a similar role to a matplotlib backend.

Advantages

Compared to Orca, Kaleido brings a wide range of improvements to plotly.py users.

pip installation support

Pre-compiled wheels for 64-bit Linux, MacOS, and Windows are available on PyPI and can be installed using pip. As with Orca, Kaleido can also be installed using conda.

Improved startup time and resource usage

Kaleido starts up about twice as fast as Orca, and uses about half as much system memory.

Docker compatibility

Kaleido can operate inside docker containers based on Ubuntu 14.04+ or Centos 7+ (or most any other Linux distro released after ~2014) without the need to install additional dependencies using apt or yum, and without relying on Xvfb as a headless X11 Server.

Hosted notebook service compatibility

Kaleido can be used in just about any online notebook service that permits the use of pip to install the kaleido package. These include Colab, Sagemaker, Azure Notebooks, Databricks, Kaggle, etc. In addition, Kaleido is compatible with the default Docker image used by Binder.

Security policy / Firewall compatibility

There were occasionally situations where strict security policies and/or firewall services would block Orca’s ability to bind to a local port. Kaleido does not have this limitation since it does not use ports for communication.

Disadvantages

While this approach has many advantages, the main disadvantage is that building Chromium is not for the faint of heart. Even on powerful workstations, downloading and building the Chromium code base takes 50+ GB of disk space and several hours. On Linux this work can be done once and distributed as a large docker container, but we don't have a similar shortcut for Windows and MacOS.

Scope (Plugin) architecture

While motivated by the needs of plotly.py, we made the decision early on to design Kaleido to make it fairly straightforward to add support for additional libraries. Plugins in Kaleido are called "scopes". For more information, see https://github.com/plotly/Kaleido/wiki/Scope-(Plugin)-Architecture.

Language wrapper architecture

While Python is the initial target language for Kaleido, it has been designed to make it fairly straightforward to add support for additional languages. For more information, see https://github.com/plotly/Kaleido/wiki/Language-wrapper-architecture.

Building Kaleido

Instructions for building Kaleido differ slightly across operating systems. All of these approaches assume that the Kaleido repository has been cloned and that the working directory is set to the repository root.

$ git clone git@github.com:plotly/Kaleido.git

$ cd Kaleido

Linux

There are two approaches to building Kaleido on Linux, both of which rely on Docker.

The Linux build relies on the jonmmease/chromium-builder docker image, and the scripts in repos/linux_scripts, to download the chromium source to a local folder and then build it.

Download docker image

$ docker pull jonmmease/chromium-builder:0.9

Fetch the Chromium codebase and checkout the specific tag, then sync all dependencies

$ /repos/linux_scripts/fetch_chromium

Then build the kaleido application to repos/build/kaleido, and bundle shared libraries and fonts. The input source for this application is stored under repos/kaleido/cc/. The build step will also

create the Python wheel under repos/kaleido/py/dist/

$ /repos/linux_scripts/build_kaleido x64

The above command will build Kaleido for the 64-bit Intel architecture. Kaleido can also be build for 64-bit ARM architecture with

$ /repos/linux_scripts/build_kaleido arm64

MacOS

To build on MacOS, first install XCode version 11.0+, nodejs 12, and Python 3. See https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/master/docs/mac_build_instructions.md for more information on build requirements.

Then fetch the chromium codebase

$ /repos/mac_scripts/fetch_chromium

Then build Kaleido to repos/build/kaleido. The build step will also create the Python wheel under repos/kaleido/py/dist/

$ /repos/mac_scripts/build_kaleido

Windows

To build on Windows, first install Visual Studio 2019 (community edition is fine), nodejs 12, and Python 3. See https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/master/docs/windows_build_instructions.md for more information on build requirements.

Then fetch the chromium codebase from a Power Shell command prompt

$ /repos/win_scripts/fetch_chromium.ps1

Then build Kaleido to repos/build/kaleido. The build step will also create the Python wheel under repos/kaleido/py/dist/

$ /repos/mac_scripts/build_kaleido.ps1 x64

The above commnad will generate a 64-bit build. A 32-bit build can be generated using

$ /repos/mac_scripts/build_kaleido.ps1 x86

Building Docker containers

chromium-builder

The chromium-builder container mostly follows the instructions at https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/master/docs/linux/build_instructions.md to install depot_tools and run install-build-deps.sh to install the required build dependencies the appropriate stable version of Chromium. The image is based on ubuntu 16.04, which is the recommended OS for building Chromium on Linux.

Build container with:

$ docker build -t jonmmease/chromium-builder:0.9 -f repos/linux_scripts/Dockerfile .

kaleido-builder

This container contains a pre-compiled version of chromium source tree. Takes several hours to build!

$ docker build -t jonmmease/kaleido-builder:0.9 -f repos/linux_full_scripts/Dockerfile .

Updating chromium version

To update the version of Chromium in the future, the docker images will need to be updated. Follow the instructions for the DEPOT_TOOLS_COMMIT and CHROMIUM_TAG environment variables in linux_scripts/Dockerfile.

Find a stable chromium version tag from https://chromereleases.googleblog.com/search/label/Desktop%20Update. Look up date of associated tag in GitHub at https://github.com/chromium/chromium/ E.g. Stable chrome version tag on 05/19/2020: 83.0.4103.61, set

CHROMIUM_TAG="83.0.4103.61"Search through depot_tools commitlog (https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/tools/depot_tools/+log) for commit hash of commit from the same day. E.g. depot_tools commit hash from 05/19/2020: e67e41a, set

DEPOT_TOOLS_COMMIT=e67e41a

The environment variable must also be updated in the repos/linux_scripts/checkout_revision, repos/mac_scripts/fetch_chromium, and repos/win_scripts/fetch_chromium.ps1 scripts.

CMakeLists.txt

The CMakeLists.txt file in repos/ is only there to help IDE's like CLion/KDevelop figure out how to index the chromium source tree. It can't be used to actually build chromium. Using this approach, it's possible to get full completion and code navigation from repos/kaleido/cc/kaleido.cc in CLion.